The story of the Piper Tomahawk an interesting one filled with unique handling and flight characteristics, accidents, investigations, divided opinions, and controversy.

The adage “be careful what you wish for because you just might get it” also applies. But before we delve into the details of this interesting aircraft, we will step back and take a look at where the Piper Tomahawk got its start.

History of Piper Aircraft

The Taylor Brothers Aircraft Manufacturing Company was started in 1927 by brothers Clarence and Gordon Taylor out of Rochester, New York.

Their first offering was a two-seat high-wing monoplane christened the Taylor Chummy. Sales were sluggish on the $4,000 plane, and in 1928 when Gordon died while flying another Taylor designed aircraft, Clarence moved the company to Bradford, Pennsylvania thanks to the town’s offer of a new factory and investment money.

One of the main investors was Mr. William T. Piper who would eventually earn the nickname “The Henry Ford of Aviation.”

Piper initially partnered with Taylor, handling the finances while Taylor continued as engineer, but a rift developed between the two and in 1937, Piper purchased Taylor Brothers Aircraft Manufacturing Company, and changed its name to Piper Aircraft.

The new Piper Aircraft company started production with their Depression-era E-2 Cub. Next up was perhaps the most legendary and prolific Piper aircraft – the Piper J-3 Cub with all of its subsequent variants including a WWII military version.

When the post-WWII boom ended, Piper’s sales declined until new military orders for the Korean War stimulated production. After the Korean War, Piper continued developing its range of aircraft.

The PA-38-112 Piper Tomahawk made its debut in 1978 and is one of the most affordable Piper aircrafts still able to be found today.

Designing the Piper Tomahawk

The design premise for the Piper Tomahawk was to create an ideal trainer aircraft that CFIs would love and want to use. To make sure they got it right and that the target market would be interested in the finished aircraft, the Piper design team sent out a survey to more than 10,000 flight instructors.

The instructors were asked to identify the physical aspects and handling characteristics that they looked for in the ideal flight trainer aircraft.

When the surveys were returned, the CFI consensus was that the ideal trainer aircraft should have “realistic” spin characteristics. It would be heavier on the controls, making the transition to other touring types of aircraft a little easier.

The fuel system should be simple, self-explanatory, and easy to access. Improved visibility and expanded cabin space rounded out the key requests.

Armed with this list of feature and handling requests, the Piper design team got to work and in 1977 the Piper PA-38-112 Tomahawk was released.

Key Design Features of the Piper Tomahawk

The Piper Tomahawk is a two-seat single-engine tricycle gear plane with low cantilever wing configuration and T-tail. In alignment with the initial premise of building the ultimate flight trainer based on target market consensus, the differentiating design features of the Tomahawk are exactly what the surveyed flight instructors requested.

Stall/Spin Characteristics

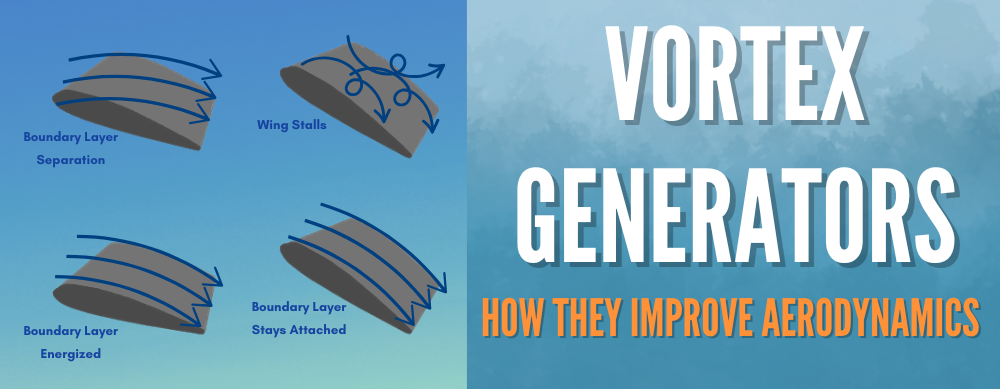

The NASA Whitcomb GAW-1 airfoil is the driving force behind the Tomahawk’s unique to its class stall/spin characteristics.

When the Tomahawk goes into a stall, it is designed so that the pilot must go through the entire textbook stall recovery procedure to get out of the stall. There are no shortcuts, and the plane is not built with self-recovery tendencies.

As you will recall, the CFIs wanted to be able to easily demonstrate spins to their students, and fortunately or unfortunately, the Tomahawk delivers on this aspect as well.

The Tomahawk tends to drop a wing when it is in a stall. Add a little yaw, mishandle the ailerons, elevator, or rudder, and a spin is liable to develop.

The merits and dangers of the Tomahawk’s stall/spin characteristics are its most debated attributes.

Heavy Controls & T-Tail

The Piper Tomahawk can be an excellent steppingstone training plane for a pilot who is working their way up to larger aircraft. Part of this is thanks to the heavier feel of the controls. They more closely mimic the handling of a much larger aircraft than that of a two-place trainer plane.

The other design feature that the Tomahawk shares with larger aircraft is its T-tail. The T-tail decreases elevator control responsiveness at airspeeds below about 35 KIAS. With proper training and awareness, this is not a concern, however pilots have been known to over-rotate on takeoff if they have been holding too great backpressure.

The inverse can occur on landing. The need for proper training and current skills in flying T-tail aircraft may explain why 61% of Tomahawk accidents have occurred during takeoffs and landings.

Still, a pilot who carefully learns about and respects the unique handling characteristics of the Tomahawk can gain valuable experience that will serve them well when they make the transition to larger aircraft.

Engine Access

On the Tomahawk, visualizing and accessing the engine is a fast and easy endeavor. The Lycoming can be reached through a wide double opening cowling. If it is necessary to remove the engine for repairs, the engine can be taken out while leaving the propeller attached. This minimizes time and labor costs for the job.

Visibility

The Tomahawk’s cockpit is outfitted with extensive wrap-around windows for nearly 360 degrees of external visibility. This plus the low-wing design makes it easier for students and newer pilots to visually locate aircraft coming down into their flight path, thus potentially preventing many mid-air collisions.

Cabin Space

To provide the maximum cabin space for the aircraft size, the Piper team opted for a bubble-shaped cockpit. This roomy cockpit is accessed via a front-hinge over-the-wing door on either side of the plane.

History of the Piper Tomahawk

Production on the Piper Tomahawk began in 1977 and wrapped in 1982 with almost 2,500 Tomahawks having been built. The Tomahawk entered the two-seater trainer market pitted against competition like the Cessna 152 and the Grumman AA-1, both of which were powered by the same Lycoming engine as the Tomahawk and had comparable payload and performance.

As a budget-conscious trainer aircraft, at $19,730, the Tomahawk was affordable, and that paired with its unique design garnered it a lot of attention early on.

Attention can be good for business, but unfortunately for Piper, upon its release, the Tomahawk started to quickly rack up a list of problems that needed to be addressed with airworthiness directives and service bulletins. There have been more than 36 airworthiness directives issued for the Tomahawk.

Piper got on top of the issues and in 1981 they released the Tomahawk II which addressed all the airworthiness directives and service bulletins to date.

This newly revised aircraft may have been enough to extend the production of the Tomahawk line, but with the concurrent aviation industry slump in the early 80’s, Piper decided to suspend production and the Tomahawk’s 5-year run came to a close with just under 2,500 planes produced.

Of those 2,500 aircraft, the vast majority are the original version with only a few hundred of the updated Tomahawk II having been produced.

Tomahawk Wing Controversy

An unfortunate saga in the Tomahawk’s story is the controversy surrounding its wings. Following a March 1994 dual fatality Tomahawk crash, the NTSB investigation revealed that there were

“--reports of significant differences in the stall characteristics between the certification-tested airplane and the production airplanes.”

They also discovered that the certification flight testing report did not show any record of turning flight stalls with extended flaps or accelerated stalls with both flap configurations ever having been tested.

After checking the records, the NTSB found that the certification testing was all done on a single pre-production aircraft and that multiple test pilots agreed that production Tomahawks were

“nothing like the article certified as far as stall characteristics are concerned.”

A Piper engineer testified that

“--shortly after delivery of production airplanes began, owners and operators of the airplane complained that the lateral directional characteristics at the stall were abrupt and unpredictable, and that the airplane exhibited a rapid roll as the stall occurred.”

Piper responded in 1979 by modifying the wing to add two additional stall strips to the existing two stall strips. This modification resulted in the issuance of AD 83-14-08, however apparently the FAA was not involved in any of the testing of the new modifications.

According to the NTSB report, a Swedish National Aeronautics Board Investigation Commission conducted their own study after a 1979 stall/spin training accident fatality and they concluded that the Tomahawk

“--did not meet the 14 CFR Part 23 certification requirements for wings-level stall characteristics.”

This outcome was the same for both the two-stall strip and the four-stall strip configurations.

Finally in 1998, the FAA responded to the NTSB report stating that they had reviewed the latest production drawings of the Tomahawk wings and compared them to those of the certification test wings which had been approved during the certification process.

The FAA concluded that everything was accounted for and that the wing design of the certification model and production models was a match.

Regarding the stall strip testing, the FAA stated that following the conclusion of the NTSB investigation, they had located the 1979 report documenting FAA involvement and documentation of satisfactory results of stall strip testing.

So, controversy officially resolved, but doubts lingered in the minds of some pilots, and the saga certainly did nothing to improve the image and reputation of the Tomahawk.

(source: images made from screenshots of the POH from ramaviation )

Flying the Piper Tomahawk

The pilot response to the Tomahawk has been, shall we say “varied.” Early on, the Tomahawk gained its unfortunate reputation and history of being prone to spin/stall accidents. This earned it dubious unofficial nicknames like “Traumahawk” and “Terrorhawk.”

Rod Machado, well know pilot and author of several well-respected flight books including Rod Machado’s Private Pilot Handbook, has this to say about the Tomahawk’s handling characteristics:

“This turned out to be one of the more peculiar training airplanes Piper invented. With its highly responsive T-tail, you could easily over-rotate on takeoff or landing and damage the empennage.”

Machado believes that the lesson learned from the Tomahawk is to not design a plane by committee and to focus on what pilots rather than CFIs want.

This brings up an interesting point with regards to aircraft design. 40% of the CFIs who Piper surveyed did indeed want an aircraft that that they could more easily demonstrate spins in. Other trainers were too hard to put into a spin and they tended to fly themselves out of it.

The CFIs wanted a plane that would help students increase their spin recovery proficiency by forcing them to make specific piloting inputs to recover from the spin.

The Tomahawk delivered on that request, but some would argue that they did it at the expense of creating more of a dedicated trainer than a solid airplane that works well as a trainer. They may also have opened the door for potential accidents.

Statistically, the Tomahawk had a fatal stall/spin accident rate of 0.336 to 0.751 accidents per 100,000 flight hours as opposed to the 0.098 to 0.134 of the comparable Cessna 150/152. This means that the Tomahawk is three to five times more likely than the Cessna 150/152 to be involved in a fatal spin accident.

(source: images made from screenshots of the POH from ramaviation )

That statistic only demonstrates part of the story, however, as the overall accident rate for the Tomahawk is just 1/3 that of the 152/152. So, the Tomahawk as originally created may have experienced a higher rate of fatal stalls/spins, but it has also proven to be a safer aircraft overall.

The AOPA Air Safety Foundation did a safety review of the Tomahawk to see if they believed its unfavorable reputation was justified. In analyzing the details of the reported stall/spin scenarios, the ASF found that,

“the vast majority of them occurred at low altitude where, by our estimate, it would have been difficult — if not impossible — to recover from an incipient spin, regardless of aircraft type.”

They go on to note,

“A common misperception is that of a student and instructor deliberately spinning the Tomahawk at a safe altitude and then becoming locked into an unrecoverable situation. Fortunately, this type of accident is an exception.”

A point of interest for the ASF was a POH revision that states,

“The immediate effect of applying normal recovery controls may be an appreciable steepening of the nosedown attitude and an increase in the rate of spin rotation. This characteristic indicates that the aircraft is recovering from the spin, and it is essential to maintain full antispin rudder and to continue to move the control wheel forward and maintain it fully forward until the spin stops."

After reviewing the details of the Tomahawk’s handling characteristics and its accident history, the AOPA ASF recommended the following:

- Pilots should be aware of the Tomahawk’s POH revision and have the patience to commit to and follow through with the appropriate control inputs in the event of a stall

- Add a bit of extra altitude margin when intentionally conducting stalls or spins

- Before soloing in the Tomahawk, have a skilled instructor with Tomahawk spin experience demonstrate the stall/spin recovery procedures

- Understand, train on, and anticipate the characteristic handling effects of the Tomahawk’s T-tail

The ASF concludes their report by stating,

“While it is easy to focus on the negative, the PA-38 has many positive traits.”

They note that the Tomahawk has excellent cockpit visibility which can help reduce midair collision potential. It also has a superior night training safety record and has been involved in half as many fuel exhaustion and starvation accidents as the Cessnas.

Despite its lingering unfavorable reputation, there are plenty of pilots for whom the Tomahawk is a preferred aircraft as long as the airworthiness directives have all been addressed and the pilot is well aware of the Tomahawk’s unique design features and handling characteristics. One of these pilots is Erasmo “Eddie” Malacara of Eddie Aviation Services.

If you are concerned about the Tomahawk’s stall/spin characteristics, watch Eddie demonstrate and discuss training spins in the Piper Tomahawk.

Eddie has practiced and perfected the technique and during the demo he talks through the process as well as the stall/spin handling differences between the Tomahawk and the Cessna 150/152.

As Eddie coaches his student through the recovery procedure, notice the instruction to hold the input since the recovery is not instantaneous. Eddie also points out that a left spin is more violent than a right spin due to P-factor and that the tail develops a signature shudder leading into the spin.

Eddie echoes the ASF advice to invest time learning and practicing spins with an experienced instructor. This goes a long way towards safer flight.

(source: images made from screenshots of the POH from ramaviation )

Variants of the Piper Tomahawk

During the final 2 years of production, Piper made multiple modifications, enhancements, and improvements to the Tomahawk design. The re-vamped aircraft was referred to as a Tomahawk II.

The Tomahawk II design featured creature comforts like improved cabin heating and better soundproofing. The windshield defrosting performance also received improvements as did the elevator trim system.

Airframe longevity was considered and enhanced thanks to the use of zinc-chromate anti-corrosion treated airframes. The final welcome upgrade was larger wheels and tires. The new 6-inch models performed better on unimproved grass and dirt runways thanks in part to the increased propeller ground clearance.

The Tomahawk II planes also came direct from the factory with all the identified airworthiness directive issues already resolved. This makes the Tomahawk II the preferred (and more expensive) variant when searching for a new-to-you Piper Tomahawk.

The Tomahawk IIs are also harder to find than the original Tomahawks because in addition to their higher demand, fewer than 500 of the nearly 2,500 Tomahawks produced were Tomahawk IIs.

Piper Tomahawk II PA-38-112 Specifications

- Engine: Lycoming 0-235-L2C

- Horsepower: 112 hp

- Propeller: Sensenich 72-inch fixed pitch 2-blade

- Length: 23 feet 1.25 inches

- Height: 9 feet 1 inch

- Wingspan: 34 feet

- Wing Area: 124.7 square feet

- Wing Loading: 13.39 pounds/square foot

- Power Loading: 14.9 pounds/horsepower

- Seats: 2

- Empty Weight: 1,128 pounds

- Maximum Gross Weight: 1,670 pounds

- Useful Load: 542 pounds

- Baggage Capacity: 100 pounds

- Fuel Capacity: 30 gallons

Piper Tomahawk II PA-38-112 Performance

- Takeoff Distance Ground Roll: 820 feet

- Takeoff Over 50 ft. Obstacle: 1,460 feet

- Rate of Climb, Sea Level: 718 feet per minute

- Top Speed: 126 miles per hour

- Cruise Speed: 115 miles per hour

- Stall Speed: 56.5 mph

- Fuel Consumption: 6.5 gallons per hour at 75% power

- Range: 539 miles

- Service Ceiling: 13,000 feet

- Landing Ground Roll: 635 feet

- Landing Over 50 ft. Obstacle: 1,544 feet

- Demonstrated Crosswind Component: 15 kts

Additional Reading Material

Piper Tomahawk PA-38 Manuals and Checklists are available at PilotMall.com

1 comment

Marta Piddington

Dear pilotmall.com owner, Thanks for the detailed post!